One in nine people housed at W.Va.’s most overcrowded, under-vaccinated jail has COVID-19

As the Delta variant drives Covid-19 to new heights across the state, an outbreak in West Virginia’s North Central Regional Jail has reached 101 active cases. Built for 564, it currently holds 842 people, making it the state’s most overcrowded correctional facility. As of Friday, one in nine people there had COVID-19.

Anita Taylor’s kitchen table is covered in handwritten notes that pertain to her daughter’s medical condition and incarceration at North Central Regional Jail in Doddridge County, W.Va. Friday, Sept. 17, 2021. (Photo/Anita Taylor)

Sept. 20, 2021 • Written by Kyle Vass

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. (Dragline)—For the past three months, every day has looked the same for Anita Taylor.

Her daughter, Callie Taylor, was taken to North Central Regional Jail in June on charges of forgery and drug possession. Shortly after she arrived, Callie developed an infection on her face. A doctor diagnosed it as Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus or MRSA—an antibiotic-resistant strain of staph the CDC has linked to overcrowded correctional facilities.

Since then, Anita has received word that Callie is among the 101 active COVID-19 cases at the state’s most overcrowded regional jail.

“I think about it all day until I go to bed. And, I wake up thinking about it,” Anita said. “Sometimes, I even wake up in the middle of the night and guess what? I’m thinking about it.”

With COVID-19 visitation restrictions in place, Anita has been relegated to the sidelines, trying to help Callie get medical treatment from her kitchen table. She hasn’t seen Callie in person for months. So, she waits for updates, checking online or sitting by the phone.

“It’s very rare that you can see my table. There’s papers everywhere,” she said.

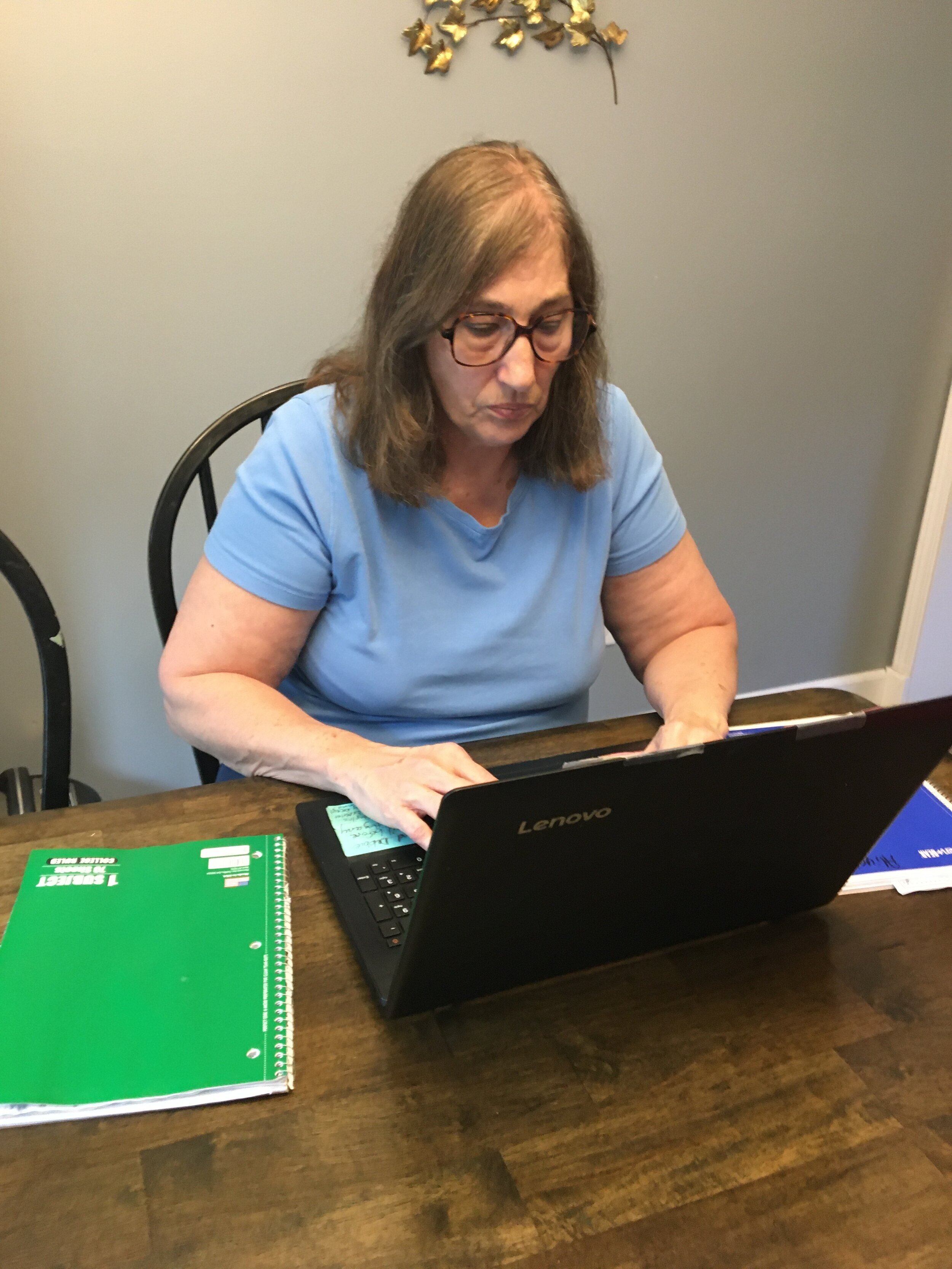

Anita Taylor uses her laptop to find updates about a COVID-19 outbreak at North Central Regional Jail where her daughter, Callie Taylor, is currently being incarcerated. Friday, Sept. 17, 2021. (Photo/Anita Taylor)

Callie’s cellmates were in the habit of calling Anita when Callie was in the medical bay, unable to call her mother herself. But, Anita began to worry because she hadn’t received an update for a few days—a Sept. 9 phone call ending with Callie saying she had told guards she was worried she had contracted COVID-19, but hadn’t been tested or seen by a medical professional.

“I try not to think of things, but my biggest thought was that they were going to call and tell us that Callie is dead,” Anita said.

When she received a video call from the jail on Sept. 11 it was one of Callie’s cellmates. She told Anita that Callie had tested positive for COVID-19. In a panic, Anita began calling the jail and local hospitals, trying to locate her daughter. But, she said no one would disclose medical information, despite Anita’s insistence that Callie had submitted paperwork to the jail giving medical professionals permission to discuss her records with her mother.

Callie called Anita the following day to say she had told the staff she thought she might have COVID-19, but that no action was taken. She wasn’t tested until the following day. According to Anita, Callie had been “walking around the general population” for an entire day between expressing her concern and testing positive.

When the call ended, Anita reached out to the Doddridge County Health Department to warn them about a potential outbreak.

“I told them, ‘I can tell you right now my daughter has it. She's been out in the general population. And I said, you're probably gonna have a mess.”

A Doddridge County Health Department spokesperson declined to comment on how the department learned of the outbreak at North Central. When reached for comment, a Department of Corrections spokesperson said all people held in state custody are isolated when they test positive.

Tracking outbreaks in West Virginia’s regional jails

The situation at North Central, where Callie is held, marks the sixth time the state's regional jail system has seen outbreaks rise beyond 100 cases. But, this is only the second triple-digit outbreak to occur in that system since the onset of the Delta variant. As, past outbreaks have corresponded with statewide trends, jail populations across the state are at particularly high risk right now.

An analysis of the five other triple-digit COVID-19 outbreaks to have occurred in West Virginia’s regional jails so far shows a significant uptick in testing was required before the number of active cases began to drop.

In past triple-digit outbreaks, active case numbers didn't start to fall until jail staff had managed to test 95% of their population within a 14-day period.

As of Friday, administrators at North Central had only tested 21.3% of the population over the previous 14 days.

For officials at North Central to keep up with past testing strategies where outbreaks have been successfully eliminated, officials will have to administer 619 tests within the next six days—a challenge made harder by the fact that 9% of employees at the already understaffed regional jails have left since the beginning of March.

America’s most under-vaccinated state

Before the arrival of the Delta variant, West Virginia’s vaccination rate plateaued around 40%. It’s currently the least vaccinated state per capita in the nation. According to the Mayo Clinic, West Virginia has the lowest percentage of people fully vaccinated between the ages of 18 and 65, coming in at just 39.1%.

Now, as the variant ravages those living in the most vaccine hesitant state, West Virginia has begun to lead the nation in new cases per capita. Considering research has shown people inside correctional facilities are four times more likely to contract the disease than people outside, surging COVID-19 numbers and a low vaccination rate paint a grim picture for incarcerated people here.

Vaccination efforts at North Central have also come up short. It ranks last among regional jails when comparing the number of vaccines administered per population at just 22.6%. This percentage, however, only reflects the number of vaccines administered at a specific jail by population as WV DCR does not keep track of vaccination status for incarcerated people.

In addition to vaccination woes, North Central is the state’s largest and most overcrowded regional jail. Callie is one of 842 people being held in a facility with only 564 beds.

Overcrowding drives countless cases across U.S.

Early in the pandemic, before there was a single case of COVID-19 in state correctional facilities, officials released incarcerated people in an effort to address overcrowding and lower the potential for outbreaks. It seemed to work—until five months later when the regional jail population surpassed pre-pandemic numbers.

Research in March conducted by Quenton King at the WV Center on Budget and Policy showed that efforts to lower the number of people in regional jails were short-lived. Prisons, which weren’t overcrowded to begin with, saw a steady decline in population. Jails, on the other hand, went from operating at 120% capacity before the state’s efforts to lower these numbers to operating at 140% capacity within a year.

The report also showed that West Virginia’s jail population has been steadily increasing over the past ten years. In 2010, the average daily population of people incarcerated in regional jails for the state was 3,929. As of today, that figure is 5,429.

These findings were corroborated in an article released today by the Marshall Project which showed West Virginia is one of only four states in the nation to have its incarceration rate increase from 2010 to 2020. The report also referenced 2020 US Census data that show West Virginia had the most severe population loss in the country--losing 3.2% of its population.

Over the last decade, West Virginia has lost tens of thousands of people while the number of people in its regional jails has increased by some 1,500 people.

Jail churn and increased COVID-19 transmission

Another risk factor linking regional jails to COVID-19 transmission is their high turnover rates. Unlike prisons in the state, people are constantly passing through the overcrowded regional jails. In a presentation to the WV Legislature last week, a representative from WV DCR told lawmakers last year 20% people who were arrested and brought into regional jails left within 24 hours of arriving.

The churn—people coming and going into overcrowded and notoriously hard to disinfect jails—resulted in millions of COVID-19 cases nationally.

Earlier this month, a study released by theJournal of the American Medical Association found 55% of people in regional jails spent less than a week incarcerated. Applying this rate of turnover to jails in West Virginia, an estimated 2,900 people are coming and going from regional jails every week as the state sees new records set for COVID-19 cases every day.

West Virginia’s new death sentence

When asked to comment on the outbreak at the jail which has jurisdiction in her legislative district, Delegate Danielle Walker highlighted the fact that most of the people held at regional jails (54.3%) aren’t there because they’ve been convicted in a court of law. They’re being exposed to deadly, preventable conditions while waiting for their day in court.

Delegate Danielle Walker of the W.Va. House of Delegates gives a speech to a crowd in Charleston, W.Va. Del. Walker represents the 51st District, one of the areas served by North Central Regional Jail. (Photo/Kyle Vass)

“Awaiting trial shouldn’t be a death sentence to anyone. It’s time that we continue to do our part by keeping all West Virginians safe. Our birthright is innocent until proven guilty. Let’s not be guilty by not protecting all. Even the incarcerated deserve healthcare.”

At the time this article was published, a WV DCR report showed 15 people have died in custody from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. But, a separate report lists a further 10 deaths for 2021 as “pending/unknown.”